Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference Threats and Answers in Poland.

Authors: Maksym Sijer, Wojciech Pokora

This report has been prepared with support from IRI’s Beacon Project. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect those of IRI.

Table of contents:

- Executive summary – 3

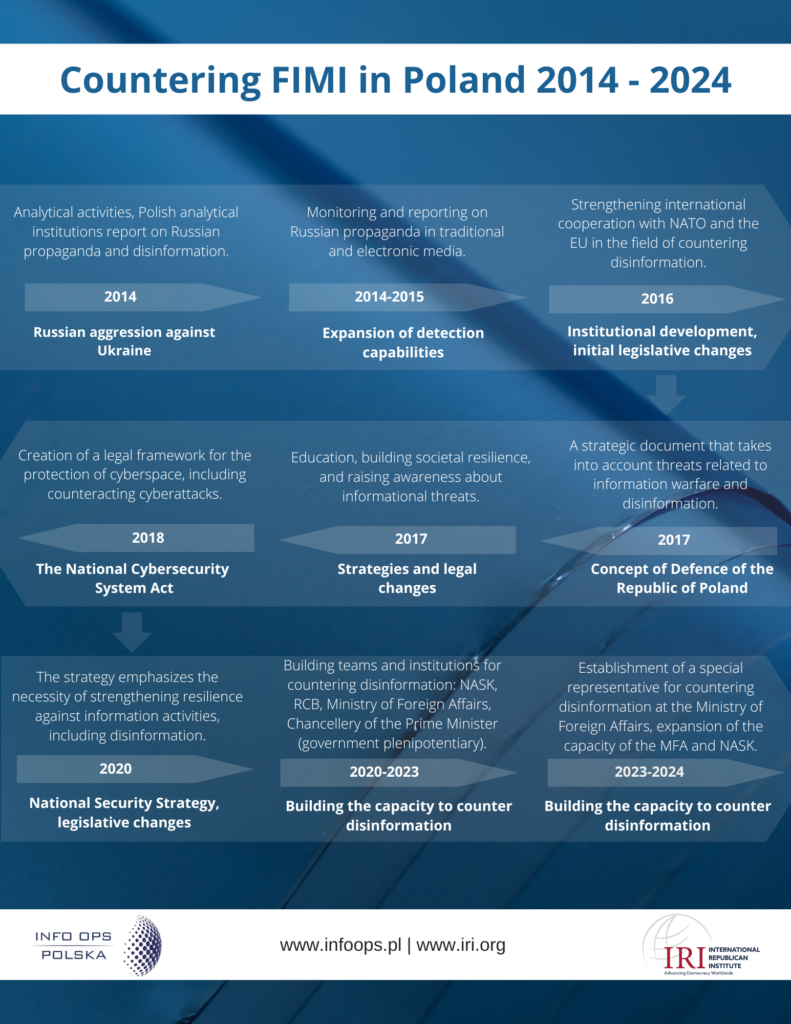

- Infographic – 5

- Introduction – 6

- Legal Framework – 7

- Institutions Responsible for Countering and Analyzing FIMI – 10

- Evolution and Dynamics of Analyzing, Reporting, and Countering FIMI – 13

- The Role of Parliament in Addressing FIMI – 16

- Key Areas and Narratives from Hostile Actors – 18

- Main Vulnerabilities Exploited by Hostile FIMI Actors – 19

- Connections and Convergences Between FIMI Actors and Domestic Entities – 22

- Is support for Ukraine at risk at the national and societal levels? – 24

- Emerging Information Threats in the Next 2-5 Years: Elections, AI, Cybersecurity – 25

- Current Gaps in Legal, Institutional, Social, and International Frameworks in Poland – 26

- How Should the National Parliament and the European Parliament Address FIMI More Effectively? – 28

- Conclusion – 31

- Attachment: Reference to Chapter 8: The spectrum of FIMI actors’ activities in the Polish infosphere (chosen aspects) – 32

Executive Summary

- The concept of Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) essentially represents an interpretation of selected aspects of active measures. Soviet active measures (Russian: активные мероприятия) refer to a broad range of propaganda, disinformation, and influence operations conducted by the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

- Countering FIMI requires coordinated efforts from both state sectors (civilian and military security) and non-governmental entities, including academia and the media. The involvement of non-governmental organizations and civil society plays a significant role.

- In Poland, the issues related to Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) do not have a direct inclusion within legal and regulatory frameworks as a closed legal act and definition.

- There are isolated regulations in Poland that, when skillfully utilized, can limit the potential for hostile FIMI operations.

- The year 2014 marked a pivotal moment when Poland, like other Central and Eastern European countries, began to intensively analyze threats related to disinformation and foreign influence, particularly in the context of Russia’s aggression towards Ukraine.

- Polish Parliamentary Committees: specialized committees, such as the Committee for Special Services, the National Defense Committee, and the Administration and Internal Affairs Committee, have the opportunity to analyze the activities of national institutions related to countering FIMI, and should do so on a regular basis and make their recommendations on state policy in this area, including publicly available reports (currently there are none).

- Issues concerning the security of the information space are inherently linked to hostile interference operations. The state’s counterintelligence capabilities, combined with the activities of both governmental and non-governmental systems, are and will be crucial in countering influence operations.

- Poland actively participates in international initiatives aimed at combating disinformation, such as those organized by NATO and the European Union, which also address legal aspects related to FIMI.

- Following the full scale invasion in Ukraine in 2022, Poland intensified its efforts to protect the information space, including organizational and legislative measures.

- In the coming years, Poland will need to confront new and evolving informational threats, including advanced technologies, election manipulation, migration challenges, and the increasing risk of cyberattacks.

- Integrated and innovative approaches will be necessary to protect against informational and psychological operations. The expansion of cybersecurity systems, the establishment of dedicated information space security teams, and effective communication strategies, alongside international cooperation, will be essential to safeguard the integrity of democracy and social stability in Poland and Western countries.

- Insufficient cooperation between institutions: Despite the presence of institutions in Poland that monitor and combat disinformation, effective coordination among various entities—including the government, media, non-governmental organizations, and social media platforms—is lacking. The high level of distrust among Poles towards the media and public institutions makes it easier for hostile entities to introduce „alternative circuits of (dis)information” and narratives that resonate with susceptible audiences and are disseminated by them.

- There are connections and alignments between internal, local actors and external entities conducting operations related to Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) against Poland.

- Although political support for Ukraine is not directly threatened, disputes among Polish political forces may influence how this topic is presented in public discourse. Hostile entities may exploit these disputes to exacerbate divisions and undermine political consensus around assistance to Ukraine.

- Lack of institutional memory: There is insufficient continuity in actions and strategies related to countering disinformation. New teams and institutions often have to start from scratch or fail to leverage prior experiences and the achievements of previous administrations.

- The European Parliament should strive to implement more comprehensive (horizontal) regulations regarding the fight against disinformation. This would entail prohibiting the dissemination of disinformation across all contexts if it poses a threat to the public interest, rather than limiting regulations to specific areas (verticality).

- Currently, differences in disinformation regulations among EU member states hinder effective coordination. The European Parliament should support the harmonization of regulations so that all countries have common standards and approaches in combating FIMI.

Introduction

Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) refers to actions undertaken by hostile foreign entities aimed at influencing public opinion, political processes (decision-making), or national security through the manipulation of information or disruptions in the flow of information.

Information Manipulation: The dissemination of false, misleading, or manipulated information to influence social perceptions or decisions. This can include disinformation (the spread of false information or selective presentation of information in a manipulated context) as well as propaganda.

Disruption of Informational Processes: Actions aimed at obstructing access to accurate information or distorting its reception. Examples may include cyberattacks on media, social media platforms, or electoral systems, as well as impersonating reputable media outlets.

The objective of FIMI is typically the destabilization of society, the erosion of trust in democratic institutions, undermining electoral outcomes, inciting social unrest, or influencing the political decisions of a country in accordance with the desires of the misleading center.

The concept of FIMI is essentially a Western interpretation of selected aspects of active measures. Soviet active measures (Russian: активные мероприятия) refer to a wide range of propaganda, disinformation, and influence operations conducted by the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The goal of these actions was to influence public opinion and political processes in Western countries and other regions of the world, aiming to weaken their governments, undermine trust in democratic institutions, and promote the interests of the USSR.

The threats posed by FIMI to Poland’s security from state actors primarily concern the active measures of the Russian Federation, China, and Belarus. Russia, continuing Soviet traditions (i.e., capabilities derived from the continuity of the security apparatus), employs various active measures against Poland, aimed at social destabilization, undermining trust in democratic institutions, and weakening Poland’s position on the international stage.

Legal Framework

In Poland, the issues related to Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) do not have a direct inclusion in the legal and regulatory frameworks as a closed legal act and definition. However, there are isolated regulations that, when skillfully utilized, can help limit the potential for hostile FIMI operations. The following events and legislative processes are particularly noteworthy:

Response to the Russia-Ukraine War (2014)

The year 2014 was a pivotal moment when Poland, like other Central and Eastern European countries, began to intensively analyze threats associated with disinformation and foreign influence, particularly in the context of Russia’s aggression towards Ukraine. The Polish government and national security institutions began to view the problem of disinformation as a threat to state security.

Amendments to Media Law and Information Protection Laws (2016-2017)

In 2016-2017, the Polish government took initial steps towards media regulation in the context of combating disinformation. Some provisions of media law were amended, and discussions commenced regarding the necessity of protecting the information space from foreign influences. Changes were also introduced regarding the protection of classified information and countering cyber threats.

Act on the National Cybersecurity System (2018)

In 2018, Poland introduced the Act on the National Cybersecurity System, which also addresses threats related to disinformation and foreign influence in cyberspace. This act encompasses actions aimed at protecting critical infrastructure and countering cyberattacks, which are often linked to disinformation campaigns.

National Security Strategy (2020)

Poland’s National Security Strategy of 2020 included clear references to threats related to disinformation and foreign influence. FIMI was identified as one of the primary challenges to national security. For the first time, the threat of FIMI received a separate chapter. The strategy emphasized the need to strengthen society’s resilience against informational manipulations and improve the capabilities of state institutions to counter these threats, in cooperation with non-governmental organizations.

Amendment to the Broadcasting and Television Act (2021-2022)

The amendment to the Broadcasting and Television Act addressed issues related to foreign capital control in Polish media. While this act was not without political controversy (example1; example2), it exemplified an attempt to regulate foreign influences within the Polish media landscape, fitting into the broader context of FIMI by appropriately addressing relevant regulations.

Increased Monitoring of Social Media

In recent years, Polish law enforcement and national security institutions have been monitoring social media to detect and counter disinformation campaigns conducted by foreign entities. In a broader context, issues related to the security of the information space are permanently associated with hostile interference operations. The state’s counterintelligence capabilities have expanded their focus to include new technology platforms that are used by hostile actors for FIMI operations.

International Cooperation

Poland actively participates in international initiatives aimed at combating disinformation, such as actions taken by NATO and the European Union, which also include legal aspects related to FIMI. At the EU level, Poland has supported initiatives concerning the regulation of online platforms (Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act) as well as the establishment of rapid response mechanisms for disinformation (Rapid Alert System).

New Legislative Initiatives (since 2022)

Following the outbreak of full-scale war in Ukraine in 2022, Poland intensified its efforts to protect the information space. Work is ongoing on new regulations aimed at further strengthening the country’s resilience to informational manipulations and foreign interference. Specifically, Article 130 of the Penal Code regarding Espionage, particularly § 9, has been supplemented with provisions concerning disinformation activities: „Anyone who, participating in the activities of a foreign intelligence service or acting on its behalf, engages in disinformation by disseminating false or misleading information aimed at causing serious disruptions to the system or economy of the Republic of Poland, an allied state, or an international organization of which the Republic of Poland is a member, or persuading a public authority of the Republic of Poland, an allied state, or an international organization of which the Republic of Poland is a member, to undertake or refrain from specific actions, shall be subject to imprisonment for a period of not less than eight years.”

Existing Laws Not Dedicated to FIMI but Potentially Usable in Its Combat

Regarding public harm caused by disinformation, a provision from Article 111 §1 of the Electoral Code currently in force in Poland addresses the dissemination of false information in connection with electoral campaigns.

Additionally, Article 180 §1 of the Telecommunications Law states: „Telecommunications operators are obliged to immediately block telecommunications connections or transmissions of information at the request of authorized entities if such connections may threaten national defense, state security, or public safety and order, or to enable those entities to carry out such blocking”. Based on this provision, the Internal Security Agency (ABW) has blocked several domains serving as conduits for Russian disinformation and propaganda since February 24, 2022.

There is also a list of domains reported by the ABW based on Article 32c of the ABW Act, which includes websites of a terrorist nature. Furthermore, in adapting Polish law to European Union regulations concerning the counteraction of disseminating terrorist content online, the Polish government has adopted a draft law allowing the head of the ABW, rather than a court as previously, to decide which content online is considered terrorist. Content may be removed based on the head of the ABW’s decision.

Article 117 of the Penal Code

Article 117 § 3 of the Penal Code states: „Anyone who publicly incites to the initiation of an aggressive war or publicly approves of the initiation or conduct of such a war is subject to imprisonment for a period of 3 months to 5 years.” This provision represents the most powerful and direct legal tool targeting entities resonating with Russian FIMI narratives since February 24, 2022. However, it remains one of the least utilized legal instruments.

Article 55 of the Law on the Institute of National Remembrance

Article 55 of the Law of December 18, 1998, concerning the Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation, stipulates that public denial of crimes referenced in Article 1, point 1 of the aforementioned law constitutes a prosecutable offense punishable by a fine or imprisonment of up to 3 years. The verdict is made public.

The acts defined in Article 1, point 1 of the law include:

a) Crimes committed against Polish nationals or Polish citizens of other nationalities from September 1, 1939, to July 31, 1990, including:

- Nazi crimes,

- Communist crimes,

- Other offenses constituting crimes against peace, humanity, or war crimes.

b) Other repressions for political motives perpetrated by officials of Polish law enforcement or the judiciary, or individuals acting on their behalf, as revealed in judgments rendered under the Law of February 23, 1991, recognizing as void the judgments issued against individuals repressed for their activities in support of an independent Polish state.

This law prohibits the denial of all crimes committed by totalitarian regimes, including both fascist and communist variants. It also pertains to the so-called „Auschwitz Lie„, referring to Holocaust denial and revisionism, which legally asserts that the commonly accepted interpretation of the Holocaust is either largely exaggerated or completely falsified. Since the law also prohibits the denial of communist crimes, it is appropriate to refer to the „Katyn Lie”.

Conclusion

All the aforementioned measures demonstrate that Poland has been gradually establishing legal and regulatory frameworks in response to threats related to FIMI, adjusting its provisions to the dynamically evolving challenges in the field of information security. Nevertheless, efforts in this area should continue to develop, both in terms of legislation and the enforcement of existing regulations. The ongoing evolution of these frameworks is essential to effectively counter the persistent and adaptive nature of disinformation threats.

Institutions Responsible for Countering and Analyzing FIMI

In Poland, the counteraction and analysis of threats related to Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) involve a range of institutions and state agencies that cooperate within various governmental structures. The main institutions include:

- DPD NASK (Department for Counteracting Disinformation NASK).

NASK (National Research and Academic Network) is a research institute under the Ministry of Digitization. In early 2022, it established the Department for Counteracting Disinformation (DPD). As of March 2024, it underwent significant changes and will focus on external threats to Poland. Due to its human and financial resources, DPD NASK bears the greatest obligation and responsibility among all civil institutions in Poland.

- Internal Security Agency (ABW)

Tasks: ABW is the principal agency responsible for protecting Poland’s internal security, including countering threats related to disinformation and information manipulation from foreign states. ABW monitors and analyzes disinformation activities and conducts operations aimed at neutralizing them.

International Cooperation: ABW collaborates with intelligence services and security agencies from allied states to effectively counter FIMI threats at the international level.

- Military Counterintelligence Service (SKW)

Tasks: SKW is responsible for safeguarding Poland’s military security, including countering disinformation and information manipulations that may threaten Polish armed forces and their operations. SKW monitors informational activities directed against Polish military interests both domestically and abroad.

- Ministry of National Defense (MOD)

Tasks: MOD, through its structures such as the MOD Operational Center and military commands, conducts activities aimed at countering disinformation in the media and online spaces. MOD coordinates activities related to cybersecurity, which also encompass protection against FIMI operations.

Cybersecurity: MOD manages national cyber defense capabilities, including protection against cyberattacks that are often linked to disinformation campaigns.

- Ministry of the Interior and Administration (MSWiA)

Tasks: MSWiA, through its agencies, including the Police and Border Guard, monitors and responds to threats related to disinformation, particularly in the context of public order and internal security. MSWiA is also engaged in educational efforts and information campaigns aimed at increasing public awareness of FIMI threats.

Information Security: MSWiA coordinates activities related to the protection of critical infrastructure and information security at the administrative level.

- Government Security Centre (RCB)

Tasks: RCB is responsible for coordinating government actions in crisis situations, including those arising from disinformation and information manipulation. RCB develops response scenarios for various forms of threats, including hybrid threats that may involve FIMI campaigns. A public document encompassing the analysis of disinformation threats is the National Crisis Management Plan (KPZK RCB).

Crisis Management: RCB collaborates with other state institutions in monitoring and analyzing threats and coordinates actions to counter these threats, which can be critical in managing incidents whose effects may negatively impact the information environment (such as disasters, terrorist attacks, and other physical incidents).

- Command of the Military Cyber Defense Component (DKWOC)

Tasks: DKWOC operates within the Polish Armed Forces and is responsible for protecting Poland’s cyberspace, including monitoring and neutralizing threats from state actors. DKWOC collaborates with other services in the exchange of information and responding to security-related incidents.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA)

In May 2024, a special envoy was appointed by the Minister of Foreign Affairs to address international disinformation. The envoy will lead the Strategic Communication Department.

Tasks: The new envoy will be responsible for implementing strategies and coordinating efforts related to the identification, monitoring, and combating of foreign disinformation. The envoy’s responsibilities include cooperation with international partners and organizations dealing with disinformation, as well as coordinating collaboration with domestic offices and institutions, along with non-governmental organizations for the exchange of information, experiences, and best practices. MFA conducts diplomatic activities aimed at countering disinformation on the international stage, including addressing FIMI campaigns directed against Poland. MFA is also involved in informing the international community about threats from foreign states.

Public Diplomacy: MFA engages in active public diplomacy, seeking to correct false information and promote an accurate representation of Poland on the international stage, including through a special grant program dedicated to countering international disinformation by non-governmental organizations.

- National Broadcasting Council (KRRiT)

Tasks: KRRiT monitors the Polish media market to ensure that broadcast content complies with Polish law, including efforts to counter disinformation and media manipulation. KRRiT also has the authority to impose sanctions on broadcasters that violate information security regulations.

Media Regulation: KRRiT is working on regulations aimed at increasing media transparency and limiting foreign influences on Polish media outlets.

- Personal Data Protection Office (UODO)

Tasks: UODO monitors the protection of personal data, which is crucial in the context of countering FIMI, as „hack and leak” operations often involve the unauthorized use of personal data. This office collaborates with other institutions to ensure privacy and data security.

- Research Institutes and Think Tanks

Over the past 10 years, there have been more than a dozen centers, working groups or institutions in Poland dealing with disinformation and FIMI analysis. Unfortunately, not all initiatives are still functioning today. The flagship initiatives and NGO centers were: „Russian V Column in Poland”; „Disinfo Digest”; „Center for Propaganda and Disinformation Analysis – CAPD”;„STOP FAKE PL”; Disinfo analysis at „The Centre for International Relation” – CSM; „INFO OPS Laboratory in Cybersecurity Foundation”; Disinfo analysis at the „Casimir Pulaski Foundation”; Analysis on disinfo at „Kosciuszko Institute”; Journalistic investigations on Russian disinformation and propaganda at „Frontstory”; An organization entirely dedicated to the fight against FIMI: „INFO OPS Poland Foundation”.

State centers for the main analysis of strategic documents and doctrines related to information warfare: „Center for Eastern Studies – OSW”; „Polish Institute of International Affairs – PISM”;

„Academic Center for Strategic Communication – ACKS”. These institutions provide analysis and reports to support the government in countering information threats. There are also NGOs dealing with disinformation and fact checking as a social phenomenon (not specifically FIMI), the largest of which is „Demagog”. The Polish Press Agency also opened a project to combat disinformation and fake news – „Fake Hunter”.

- National Cybersecurity Team (CERT Polska)

Tasks: CERT Polska is a computer incident response team operating under NASK. CERT Polska monitors and responds to threats in cyberspace, including indirectly addressing incidents that may be elements of foreign influence operations (such as website fraud, spoofing, and other internet scams).

Each of the aforementioned institutions plays a key role in protecting Poland’s information space from threats associated with FIMI, functioning both independently and within a broader framework of inter-agency and international cooperation.

Evolution and Dynamics of Analyzing, Reporting, and Countering FIMI

The evolution and dynamics of analyzing, reporting, and countering Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) in Poland since 2014 reflect the growing awareness of threats related to disinformation and the need to respond to increasingly sophisticated and complex influence operations from third countries, particularly Russia.

1. Initial Phase (2014-2016): Awareness of Threats and First Responses

Geopolitical Context

Russia’s war against Ukraine (2014) and the annexation of Crimea heightened concerns in Poland regarding disinformation and manipulation efforts conducted by Russia in Central and Eastern Europe. Russia extensively utilized propaganda tools to justify its actions in Ukraine, raising awareness in Poland about potential threats.

First Actions

Think Tank Analyses: Polish analytical institutions, such as the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW, state entity), the INFO OPS Poland Foundation (NGO), and the Polish Institute of International Affairs (PISM, state entity), and other listed NGOs on the previous page, began to intensively study and report on Russian propaganda and disinformation in the region. The first fact-checking organizations, such as Demagog PL (NGO), were also established.

Media Monitoring: The initial systematic efforts to monitor the information environment and the influence of Russian propaganda directed at Polish society commenced, alongside research and analysis of propaganda narratives.

2. Consolidation Phase (2016-2018): Institutional and Strategic Development

Institutional Strengthening Amendment to the National Cybersecurity System Act:

In 2018, legislation was adopted that established a legal framework for protecting Poland’s cyberspace, including countering cyberattacks and disinformation. The creation of the CSIRT (Computer Security Incident Response Teams) network was significant in defending against FIMI operations by systematizing and organizing incident response processes in cyberspace, particularly for cyberattacks that may be components of influence operations.

Strategies and Policies

National Defense Concept (2017): This document addresses threats related to information warfare and disinformation, emphasizing the need to build the state’s resilience against such attacks. Strengthening International Cooperation: Poland has intensified its cooperation with NATO and the EU to counter disinformation, which has led to participation in joint monitoring and analysis projects regarding influence operations.

3. Advanced Response Phase (2018-2020): Development of Tools and Social Engagement

National Security Strategy (2020)

Incorporation of Hybrid Threats: This strategy highlighted the necessity of enhancing resilience to informational actions, including disinformation, in response to increasing threats from Russia.

Education and Public Awareness: There was a rise in government involvement in information and educational campaigns aimed at increasing societal resilience against disinformation.

4. Intensive Combat Phase (2020-2023): Systematization and Digitization of Actions

New Tools and Technologies Development of Analytical Tools: Poland introduced more advanced monitoring and data analysis technologies that enable quicker detection and analysis of disinformation campaigns.

Collaboration Platforms: The development of inter-institutional collaboration platforms, including partnerships with the private sector and international organizations, improved coordination of efforts.

New Institutions and Initiatives

Government Security Centre (RCB): Enhanced RCB functions in responding to information crises and the introduction of an early warning (publicly available component – #Disinfo Radar) system for disinformation campaigns (2021 – 2024).

Appointment of a Government Plenipotentiary for Information Space Security (2022 – 2023): This role included the coordination, analysis, and counteraction of disinformation at the state and inter-ministerial level.

Establishment of a Specialized Course at the Cybersecurity Expert Training Center of the Ministry of National Defense (MOD) in INFO OPS. Initiatives at military universities including the establishment of an “Information Security and Cyber Security” degree program for civilian students at the War Studies University.

Creation of a Specialized Unit for Combating International Disinformation within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (since 2023): In 2024, this unit was transformed into a department and strengthened in terms of staffing and organization.

Establishment of DPD at NASK (2022) and expansion of the Department for Counteracting Disinformation team at NASK (since 2024).

Social and Educational Initiatives

Information Campaigns: The Polish government has conducted campaigns aimed at educating the public about recognizing disinformation and false narratives. Selected examples include:

The campaign of the General Staff of the Polish Armed Forces titled „#PSYCHOodporni to #DEZINFOodporni” (2024 – currently ongoing), which is the only active information and educational campaign at present (example).

Campaigns and Initiatives:

- „Don’t Be Fooled, Check Before You Believe” (2023, Ministry of Digitization).

- NASK Program „Turn on Verification” (from February 2022 to April 2024).

- „Responsible for Words” (Panoptykon Foundation – NGO).

- #StopFakeNews (Polish Police).

- Disinfo Radar (2022 – 2024, Government Security Centre)

- „Stop Fake News” Campaign (2020): During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ministry of Health initiated this campaign.

- „Find the Right Source” (2021, Ministry of Health).

TV stations and programs dedicated to fighting disinformation and building awareness:

- Biełsat TV (ang. Bielsat TV) – TV station broadcasting in Belarusian, Russian and Ukrainian languages. Belsat provides Belarusians with access to independent information about the situation in their country and in the former USSR countries: 2007 – ongoing;

- TVP Info: „Demaskatorzy” (ang. „Demascators”): June 2023 – December 2023;

- TVP Info: „Sprawdzamy” (ang. „Verifying”): June 2024 – ongoing;

- TVP World: „The Anatomy of Disinformation”: September 2024 – ongoing.

Support for Non-Governmental Organizations: The Ministry of Foreign Affairs has established a grant program for NGOs (since 2023) aimed at combating international disinformation (example from 2024).

The evolution and dynamics of Poland’s actions regarding FIMI since 2014 demonstrate that the country is striving to respond to increasing threats through institutional, legislative, and technological development. Future challenges related to disinformation will require ongoing adaptation and innovative solutions in this area.

The Role of Parliament in Addressing FIMI

The Polish Parliament, consisting of the Sejm and the Senate, plays a significant role in countering Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) through its legislative, oversight, and political functions. Here are the key areas in which the parliament (and its members) can and should play roles:

- Legislative Function

Law Enactment: The Polish Parliament is responsible for passing laws that regulate issues related to information security, cybersecurity, and protection against disinformation threats. It establishes the legal framework that enables services, institutions, and agencies to operate in countering FIMI.

Amendments to Laws: In response to new threats, Parliament can introduce amendments to existing laws, adapting them to the dynamically changing information and technological environment.

- Oversight Function

Government Oversight: Parliament oversees government actions, including those of agencies and services involved in information security and disinformation countermeasures. This may include organizing hearings, informational sessions, and debates to discuss government actions and the effectiveness of its initiatives.

Parliamentary Committees: Specialized committees, such as the Committee for Special Services, the National Defense Committee, and the Administration and Internal Affairs Committee, have the opportunity to analyze the activities of national institutions related to countering FIMI and can present their recommendations regarding state policy in this area.

- Political Function

Public Debate: Parliament serves as a forum for public debate on threats related to FIMI. Representatives of various political parties discuss ways to protect the Polish information space, which can lead to the formulation of state strategies and policies.

Supporting Public Awareness: Through their activities, Members of Parliament and Senators can raise public awareness about the threats posed by disinformation, informational manipulations, and foreign influences, which is crucial for building societal resilience to such threats.

Budget Approval

Funding Activities: Parliament plays a key role in approving the state budget, including funds allocated for information security and cybersecurity activities. This enables Parliament to influence the level of funding for institutions responsible for countering FIMI.

- International Initiatives

International Cooperation: By participating in international parliamentary organizations and collaborating with the parliaments of other countries, Polish parliamentarians can support and initiate international efforts to counter disinformation and informational manipulations.

- Political Accountability

Debates and Interpellations: Members of Parliament and Senators can pose questions to the government and initiate debates regarding actions related to protecting Poland from FIMI, providing society with insight into the measures being taken in this sphere.

- Educational Initiatives

Educational and Social Projects: Parliament can support or initiate educational projects aimed at raising public awareness about disinformation and the threats associated with informational manipulations.

8. Initiatives for Analyzing the Impact of FIMI on Social, Political, and Economic Life in Poland

In the past two years, two successive commissions have been established:

- State Commission for Investigating Russian Influences on the Internal Security of the Republic of Poland (2007-2022) (no longer functioning).

- State Commission for Investigating Russian and Belarusian Influences (2004-2024) – established by the Prime Minister’s order (currently operational).

All these actions position the Polish Parliament as a key actor in shaping state policy and strategy regarding protection against threats related to FIMI, both at the national and international levels. At the same time, it should be assessed that the above-mentioned opportunities are not used at a sufficient level and Polish parliamentarians are not very involved in activities in this area. The fight against FIMI in the parliament is still perceived in the general consciousness as at best a fight against fake news, which is ineffective.

Key Areas and Narratives from Hostile Actors

Here are some of the most significant FIMI actions that Russia employs against Poland:

- Manipulating the narrative of Russian aggression against Ukraine, presenting

it as a purported defensive war by Russia against the West/NATO. - Psychological pressure through intimidation – nuclear blackmail.

- Energy crisis blackmail.

- Propaganda campaigns targeting the image of the Polish Armed Forces and Polish defense policy.

- Manipulating the history of World War II.

- Anti-NATO and anti-American propaganda.

- Disinformation related to COVID-19.

- Inciting social and political tensions.

- Disinformation campaigns aimed at Ukraine.

- (Dis)Information and cyber attacks on Polish media and journalists.

Exploiting the migration crisis (the forced migration mechanism used by Russia and Belarus against Poland and the Baltic states). - (Dis)Information attacks on Poland’s international image.

- Supporting extreme right and left movements (polarization).

- Fomenting anti-immigrant sentiments.

- Supporting anti-system movements.

Selected Attacks on Digital Infrastructure

- Attack on Government Infrastructure (June 2021) [example].

- Attacks on Polish Media and Companies (2022) [examples 1; 2].

- Attack on the Health Sector (2022) including hospitals [example].

- Attack on Critical Infrastructure Systems (2023) [examples 1; 2].

- Phishing Campaigns Against Officials and Entrepreneurs (2022-2023) [example].

- Attacks on the Railway Transport Sector (2023) [example].

- Attack on the Polish Press Agency (May 2024) [example].

- Hackers’ Attack on the Polish Anti-Doping Agency (POLADA) (August 2024). Hackers supported by hostile state services stole and published sensitive data of Polish athletes, totaling nearly 250 gigabytes. This attack was intended to serve as a precursor to attacks on other state institutions [example].

Further elaboration on the identified areas of hostile FIMI activity can be found in Appendix 1.

Main Vulnerabilities Exploited by Hostile FIMI Actors

In Poland, as in other countries, hostile entities engaged in Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) can exploit specific vulnerabilities characteristic of the Polish media, political, and social systems. The main vulnerabilities that can be exploited in Poland include:

Political Polarization

- Strong Political Divisions: Poland has a high level of political polarization, which creates a fertile ground for the spread of disinformation. Hostile entities can exploit these divisions and emotions by publishing false information that exacerbates conflict between various political and social groups.

- Political polarization also pertains to the attitudes of specific groups (and the social groups behind them) toward international cooperation and Poland’s participation in various international organizations. The narrative is manipulated regarding existing obligations, duties, and benefits that have already been achieved or could be realized in the future, as well as how Poland would appear without involvement in certain formats, such as NATO or the EU.

- Anti-EU and Anti-Western Narratives: Hostile entities promote narratives criticizing the European Union, NATO, and the broader West, undermining trust in international institutions and attempting to influence public attitudes toward international cooperation.

Weaknesses of the Media System

- Media Dependence on Politics: In Poland, some media outlets are aligned with specific political forces, which fuels polarization and creates social divisions rather than cohesion. Disinformation can be disseminated when media favoring a particular political narrative fail to adequately verify content or deliberately amplify controversial topics.

- Lack of Trust in Media: The high level of distrust among Poles towards the media and public institutions makes it easier for hostile entities to introduce „alternative circuits of (dis)information” and their own narratives, which resonate with susceptible audiences and are disseminated by them.

Social Media and Information Consumption Habits

- Rapid Spread of Unverified Information: In Poland, social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter/X, and TikTok serve as primary channels for disinformation. Specific ecosystems for disseminating disinformation are created on Telegram. Hostile entities can manipulate (influence) the algorithms of these platforms to ensure that false content spreads quicker and reaches a wider audience.

- Lack of Effective Content Moderation: The absence of effective content moderation in Polish on international social media platforms allows for the proliferation of disinformation without swift intervention. False information can circulate for extended periods before being identified and removed.

Security-Related Narratives

- Disinformation Regarding the Conflict in Ukraine: The inverted logic of concepts is a common manipulative tactic used by Kremlin authorities, aiming to preempt accusations and attribute blame for their actions to the opposing side. In the Kremlin’s propaganda lens, the West and Ukraine are portrayed as responsible for the war, its course, and its casualties. This constitutes disinformation about the West’s and Ukraine’s responsibility for the war, as the Russian propaganda system continues to shape a false narrative of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.

- Anti-Ukrainian Narratives: Hostile entities exploit tensions between Poland and Ukraine, drawing on historical grievances and contemporary issues to weaken solidarity against Russian neo-imperialism in the region.

- Modernization and Expansion of the Polish Armed Forces: This is misrepresented by hostile entities in a false light. Disinformation involves instilling the public with the false narrative that Poland is preparing for offensive actions against its eastern neighbors, such as Belarus, Russia or even Ukraine.

Lack of Media Education

- Low Awareness of Disinformation: In Poland, despite the growing awareness of the issue, media education is not yet sufficiently widespread. Society often struggles to recognize false information and differentiate credible sources from manipulations, which facilitates the spread of disinformation by hostile entities. Despite information campaigns there is still a lot to be done.

- Lack of Information Verification Tools: Although there are fact-checking organizations, their reach does not encompass the entire society, leaving room for hostile narratives. It is also important to note that the actual capabilities of fact-checking in countering FIMI are significantly limited and inadequate (FC is to combat disinformation as a social phenomenon, when FIMI refers to the operation of the state apparatus and secret services).

Exploitation of Social and Economic Crises

- Economic Crises and Inflation: In situations of economic crisis, such as high inflation or labor market issues, hostile entities can manipulate facts, spreading disinformation that increases social anxiety and triggers panic.

- COVID-19 Pandemic: During the pandemic, many false narratives about vaccines, the virus, and government restrictions circulated in Poland, which hostile entities actively used to undermine trust in healthcare services and state institutions.

Migration Issues

- Disinformation Regarding Refugees and Migrants: There is a lack of distinction between refugees and migrants, particularly concerning the aggression of Alexander Lukashenko’s regime (and more broadly, the Russian-Belarusian union state) below the threshold of war (hybrid threats/warfare). This strategy aims to create a humanitarian crisis to subsequently achieve political and financial objectives through informational operations (INFO OPS) and psychological pressure (PSY OPS).

- Migration issues and associated problems are exploited by Russian propaganda to construct an image of a “declining Europe and a rotting West.” This involves exaggeration and false information regarding migration, refugees, and the potential threats related to these topics.

Lack of Coordinated Institutional Response

- Insufficient Cooperation Among Institutions: Although institutions in Poland monitor and combat disinformation, there is a lack of effective coordination among various entities, including the government, media, non-governmental organizations, and social media platforms.

Anti-American Narratives

- Undermining Poland-US Relations: Hostile entities consistently attempt to undermine Poland’s cooperation with the United States, particularly in the areas of security and military collaboration, suggesting that Poland is becoming dependent on the U.S. in a manner that could be detrimental.

Use of Historical Grievances

- Manipulating Difficult History: Hostile entities may exploit historical grievances, such as Polish-Russian or Polish-Ukrainian relations, to spread disinformation, attempting to incite antagonisms between Poles and their neighbors, which leads to divisions in the region.

Connections and Convergences Between FIMI Actors and Domestic Entities

There are connections and convergences between internal, local actors and external entities conducting Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) activities against Poland. This is particularly evident in the context of conscious or unconscious cooperation between internal groups and external actors seeking to undermine Poland’s political, social, and economic stability.

1. Common Interests

- Shared Goals: Some internal groups in Poland, including extremist political movements or organizations operating on the fringes of the political scene, may have objectives aligned with those of external actors. For instance, far-right or far-left groups may be interested in destabilizing the political system, which aligns with the FIMI objectives of states such as Russia.

- Promoting Social Divisions: External FIMI actors often aim to deepen social divides, which may benefit certain local groups that also seek to polarize society. These groups may inadvertently become instruments in the hands of external actors, fulfilling their agendas.

2. Tools and Methods of Cooperation

- Disinformation Campaigns: Local groups or media often replicate narratives inspired by or originating from external FIMI actors. These narratives may relate to criticism of NATO, the EU, migration, or national and ethnic minorities. External FIMI actors utilize these topics to reinforce divisions within Poland.

- Exploitation of Social Media: External actors, especially Russia, are known for using social media to disseminate disinformation. Local actors, including extremist groups, may leverage the same platforms to spread similar content, increasing their reach and effectiveness.

- Funding and Support: Although direct evidence is scarce, there are indications that some local organizations may receive direct or indirect support from external actors. For example, funding from entities linked to Russian interests may flow to organizations or media outlets promoting narratives aligned with Russian propaganda.

3. Manipulation of Information and Narratives

- Exploitation of Local Issues: External FIMI actors frequently exploit existing social or political issues in Poland to amplify tensions. Local actors, particularly those with radical views, may use the same narratives to gain support or strengthen their influence.

- Fake Accounts and Bots: External FIMI actors, especially from Russia, often utilize fake accounts and bots on social media to amplify local narratives. These narratives are then picked up by local actors, creating the illusion of widespread support for certain views or disinformation.

4. Extremism and Radicalization

- Far-Right and Far-Left Groups: Extremist groups on both ends of the political spectrum in Poland may be inspired by or directly supported by external actors.

- Anti-Western Narratives: Local actors promoting anti-Western narratives, often aligned with Russian propaganda, may inadvertently (or deliberately) support FIMI objectives. Such narratives may involve criticism of NATO, the European Union, or the United States, or discourage resistance to Russian aggressive policies.

5. Examples of Specific Cases

- Anti-Vaccine Narratives: During the COVID-19 pandemic, external FIMI actors, particularly Russia, intensified disinformation campaigns regarding vaccines. In Poland, local anti-vaccine groups often replicated the same false information, indicating a convergence of interests.

- Disinformation Regarding the Conflict in Ukraine: Russia actively propagates false information about the war in Ukraine, and some Polish media or organizations aligned with the far-right or far-left replicate these narratives, suggesting interdependence between local and external actors.

Summary

- Complexity of Connections: The links between internal and external actors conducting FIMI against Poland are complex and often subtle. They may include shared goals, the use of similar tools and methods, as well as direct or indirect financial and organizational support.

- Importance of Monitoring: It is crucial to monitor these connections to better understand how external information operations can influence internal political and social processes in Poland. Identifying and countering these connections requires cooperation among various state institutions, non-governmental organizations, the private sector, and civil society.

Is support for Ukraine at risk at the national and societal levels?

While political support for Ukraine in Poland remains stable, societal support may be under threat due to several key factors:

- Disinformation Campaigns: These are a primary tool used to undermine public support for Ukraine. Hostile actors, such as Russia, actively spread false information aimed at fostering animosity towards Ukraine and destabilizing Polish-Ukrainian relations.

- Political Polarization: Although political support for Ukraine is not directly threatened, disputes among Polish political forces can influence how the issue is portrayed in public discourse. Hostile actors may exploit these disputes to exacerbate divisions and undermine the political consensus around aiding Ukraine.

- Lack of Effective Communication and Cooperation: The absence of effective communication and cooperation in addressing sensitive topics (e.g., historical, economic, or agricultural issues) creates opportunities for disinformation. Hostile groups can exploit contentious issues, further complicating the perception of public support for Ukraine in Poland.

- Fatigue: Over time, the public may exhibit fatigue with supporting Ukraine, especially in the face of domestic challenges such as inflation, the energy crisis, or other economic difficulties. Disinformation can exploit these issues, fueling the sentiment that Poland should focus more on its own problems rather than engaging in assistance to Ukraine.

To maintain strong public support, more effective measures are needed in media literacy education, increasing societal resilience to manipulation, and a more coherent communication strategy between Poland and Ukraine.

Emerging Information Threats in the Next 2-5 Years: Elections, AI, Cybersecurity

In the coming years, Poland will have to face new and evolving information threats that encompass advanced technologies, election manipulation, migration challenges, and the increasing risk of cyberattacks. Integrated and innovative approaches will be necessary to protect against informational and psychological operations. The enhancement of cybersecurity systems, the establishment of dedicated information security teams, and effective communication strategies, alongside international cooperation, will be essential to safeguard the integrity of democracy and social stability in Poland and Western countries.

Looking ahead, Poland will need to address several significant information threats that could greatly impact the country’s stability over the next 2-5 years. Here are the main concerns:

- Election Manipulation: The presidential elections in Poland and the United States will be targets of intense disinformation campaigns. False information regarding electoral irregularities, attempts to undermine election results, and discouraging voter turnout may be employed to challenge the legitimacy of democratic processes.

- (Des)Information Activities Related to Migrant Relocation to Poland: This area will certainly be exploited by hostile entities, and Polish state institutions should be prepared in advance.

- Dissemination of Disinformation to Global South Countries: Spreading disinformation about Poland to countries in the Global South and constructing a false image of Poland could lead to increased tensions, disrupt Poland’s interests in the region, and foster hostility towards migrants even before their arrival in Poland or broader Europe.

- Deepfake and Deepporn Technology: Deepfake technology can be used to create realistic but false video and audio materials, potentially leading to serious abuses and the compromise of public figures. Deepporn, or fake pornographic materials, may be used for blackmail or discrediting individuals.

- Automated Botnets: The development of more advanced botnets capable of generating and disseminating disinformation in multiple languages, with better translation and more personalized content.

- Mass Content Generation by AI: Automated content generation systems can be employed to produce and distribute large quantities of disinformation, making the identification of false information more challenging.

- Spoofing: Techniques such as voice spoofing, phone number spoofing, and impersonation can be used to conduct fraud, blackmail, and manipulation, impacting the privacy and security of both public and private individuals.

- Data Resource Attacks and System Compromise: Operations such as “ghostwriter” or hack-and-leak activities may involve attacks on personal data and the compromise of communications, leading to the use of this data for spreading disinformation and influencing public opinion.

- Social Divisions: Hostile entities will intensify social polarization, particularly by exploiting issues such as migration, security, and historical matters to deepen divisions and introduce chaos within society.

- Undermining International Alliances: Hostile entities will continue disinformation campaigns aimed at weakening international alliances, such as NATO, by creating false narratives regarding defense capabilities and military cooperation.

- Continuation and Possible Escalation of Activities on the Poland-Belarus Border.

- Increased Intelligence Activity: A rise in spies, akin to the model of Pablo Gonzalez [link], infiltrating European circles to sow division and discredit influential environments, including journalism.

- Heightened Informational and Psychological Activity by Russia, Belarus, and China, including the use of active measures, intelligence, and special operations.

Current Gaps in Legal, Institutional, Social, and International Frameworks in Poland

In Poland, there is a lack of solutions regarding legislation, institutional strategies, education, social cooperation, and international coordination in the fight against disinformation and FIMI threats. It is essential to develop and implement effective legal provisions, improve coordination between the government and NGOs, increase investments in combating disinformation, and enhance media education. An integrated approach at both national and international levels is necessary for effective defense against rising information threats. The main areas requiring urgent attention include:

1. Insufficient Institutional Focus

There is a need for standardization and enhancement of institutional and governmental strategies for combating disinformation. Developing and implementing a long-term strategy for countering FIMI at the inter-ministerial level is essential.

2. Lack of Institutional Memory

There is inadequate continuity in actions and strategies related to countering disinformation. New teams and institutions often fail to sufficiently leverage previous experiences and the established achievements of earlier administrations.

3. Training and Qualification of Personnel

The training system for qualified personnel involved in analyzing and countering disinformation requires organization, expansion, and standardization.

4. Lack of Standardization in Terminology and TTP (Techniques, Tactics, Procedures)

There is insufficient unification of standards and procedures for combating disinformation.

5. Communication Strategy (Stratcom)

The challenges to the security of the information environment require improvements in communication between the government and citizens regarding disinformation threats. Society should be systematically informed about how to recognize and respond to false information. Stratcom should also implement comprehensive coordination of the state’s informational activities, as well as efforts to counter disinformation both domestically and internationally.

6. Cooperation with Non-Governmental Organizations

Collaboration between the state and NGOs engaged in media education and combating disinformation should be intensified and coordinated to enhance effectiveness.

7. Educational Initiatives

There is a need to increase efforts in media education, particularly in schools and through informational campaigns conducted by various state institutions according to their areas of responsibility (e.g., health, security, international policy, internal security).

8. Legislation Regarding FIMI

Legal provisions aimed at combating disinformation and information manipulation require development. Existing regulations are often not suited to the specifics of contemporary threats, such as deepfakes or automated disinformation campaigns, active measures, or informational and psychological operations.

9. Insufficient Utilization of Existing Regulations

Existing regulations are often underutilized or applied in a limited manner. For example, the effectiveness of enforcement of disinformation laws related to glorification of the war of aggression or anti-vaccine activities is low.

10. Lack of Regulations for Combating Disinformation

There are no effective regulations for monitoring and combating false information in the media. Introducing regulations governing media actions in the context of disinformation, similar to regulations in banking (AML – Anti–money laundering – internal control departments), could improve the situation.

11. Low Financial Investment

In Poland, as in other countries, there is a need to increase financial investments in combating disinformation and FIMI. Greater investments in technology, research and development, and support for relevant institutions in both the public and non-governmental sectors are crucial.

How Should the National Parliament and the European Parliament Address FIMI More Effectively?

To more effectively combat the threats posed by FIMI, both the national parliament and the European Parliament should implement more coherent and horizontal regulations that consider collaboration with the private sector, NGOs, and international institutions such as NATO. Improved monitoring mechanisms, increased training, and effective sanctions against entities spreading disinformation are also crucial. The actions should particularly encompass:

1. Planning and Vision

The national parliament should require the government to create a clear, long-term strategy for countering FIMI. These actions should involve all levels of government, from the Prime Minister to the President, with well-defined objectives, budgets, and evaluation criteria.

2. Evaluation and Accountability of Institutions

It is essential to implement mechanisms for monitoring the effectiveness of public institutions’ actions. Parliament should regularly assess whether the relevant institutions are delivering results in the fight against disinformation.

3. Countering Fragmentation of Knowledge

Parliament should support initiatives aimed at better coordination of actions among state institutions. These efforts should focus on knowledge sharing, avoiding task duplication, and establishing a central management center for combating disinformation.

4. Collaboration with the Private Sector and NGOs

Collaboration between the government, the private sector (especially media), and non-governmental organizations should be key. Parliament can promote legislative initiatives that encourage this type of cooperation, for example, through joint educational or research programs.

5. Training and Development of Personnel

Parliament should seek to increase investments in training personnel, including public and private sector employees, in recognizing and combating FIMI. Cooperation with NATO could be particularly beneficial, especially concerning training on Russian, Belarusian, and Chinese disinformation methods.

At the European Union Level: Strengthening Regulations and Coordination

1. Horizontal Regulation of Disinformation

The European Parliament should aim to introduce more comprehensive (horizontal) regulations for combating disinformation. This would involve prohibiting the dissemination of disinformation in all contexts if it poses a threat to the public interest, rather than limiting regulations to specific areas (verticality), such as COVID-19.

2. Standardization of Regulations in the EU

Currently, differences in disinformation regulations among EU member states hinder effective coordination. The European Parliament should support the harmonization of regulations to ensure that all countries have common standards and approaches

in combating FIMI.

3. Monitoring the Effectiveness of Sanctions

The European Parliament should strengthen monitoring mechanisms for the effectiveness of sanctions against disinformation media, such as RT or Sputnik. The Rapid Alert System (RAS) should be made more effective, and member states should periodically report on actions taken to close loopholes that allow for the dissemination of Russian propaganda.

4. Mechanism for Reporting Propaganda in Other Countries

A formal mechanism should be established to allow member states to report cases of sanction violations or disinformation propaganda in other EU countries, with the possibility of taking consequences. Examples could include actions by RT in Germany, Spain or Hungary.

Responsibilities in Countering Disinformation

Compliance in Media: Just as banks are required to combat money laundering, media organizations should have the obligation to establish internal departments dedicated to countering disinformation. The European Parliament could introduce regulations that require media outlets to implement safeguards against the dissemination of false information, with penalties for non-compliance.

Penalties for Disseminating Disinformation: Media outlets that fail to implement appropriate safeguards or intentionally spread disinformation should face substantial financial penalties, which would serve as a deterrent.

Improved Exchange of Experiences and Training

EU-NATO Cooperation: The European Parliament and NATO should strengthen their collaboration in knowledge exchange and training regarding FIMI. NATO possesses extensive experience in analyzing the methods employed by Russia, Belarus, and China. The EU should leverage this potential to train its personnel in countering informational threats.

Building Defensive Capacities:

Enhancing the Capacities of EU Countries: The European Parliament should support investments in infrastructure and technologies aimed at monitoring and combating disinformation, particularly in countries more vulnerable to FIMI threats. Such initiatives could be co-financed by EU funds.

Conclusions

Poland is a target of Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) activities, particularly from Russia, Belarus, and China. The primary objective of these operations is to destabilize society, undermine trust in democratic institutions, provoke social unrest, and weaken Poland’s international standing.

In response to the FIMI threat, Poland has implemented new legal regulations, such as those related to cybersecurity, revised media laws, and supported international initiatives within NATO and the EU. Institutions such as the Internal Security Agency (ABW), the Ministry of National Defense (MOD), the Ministry of Interior and Administration (MSWiA), and NASK play crucial roles in countering disinformation, and new institutions have recently been established to monitor and address information threats.

Despite these efforts, many gaps remain in Poland that hostile entities can exploit. The main challenges include political polarization, weaknesses in the media system, a lack of media education, and insufficient cooperation among institutions and non-governmental organizations in combating disinformation.

Attachment: Reference to Chapter 8: The spectrum of FIMI actors’ activities in the Polish infosphere (chosen aspects).

Russia, continuing Soviet traditions (i.e., capabilities stemming from the continuity of the security apparatus), employs various active measures against Poland aimed at social destabilization, undermining trust in democratic institutions, and weakening Poland’s position on the international stage.

It utilizes the following actions to achieve these goals:

1. Disinformation and Propaganda

Disinformation Campaigns: Russia conducts intensive disinformation campaigns designed to sow confusion, polarize society, and create misperceptions through a wide range of propaganda and manipulation tactics.

In recent years, Russia has carried out a series of propaganda activities targeting Poland, aimed at social destabilization, undermining trust in democratic institutions, manipulating historical narratives, and weakening Poland’s position on the international stage. Here are some key examples:

- Manipulation of World War II History

- Narratives Blaming Poland: Russia has regularly attempted to reshape historical narratives surrounding World War II, particularly regarding the outbreak of the war and the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Russian authorities and media have repeatedly accused Poland of complicity in the outbreak of the war, claiming that Poland allegedly collaborated with Nazi Germany.

- The Issue of Poland’s Liberation: Russian propaganda has emphasized the role of the Red Army as liberators of Poland, while ignoring Soviet crimes such as the Katyn massacre, the deportation of Poles to Siberia, and the occupation of eastern Polish territories after the war.

- Anti-NATO and Anti-American Propaganda

- Criticism of the US and NATO Military Presence in Poland: Russian media and officials have regularly criticized the presence of NATO and US troops in Poland, portraying it as a threat to regional security. Narratives suggesting that Poland is a “puppet of the West”, acting against its own national security interests, have been frequently promoted.

- Fomenting Anti-Americanism: Russian propaganda has attempted to strengthen anti-American sentiments in Poland, suggesting that the United States is using Poland as a tool to advance its interests in Europe at the expense of the country’s security and sovereignty.

- Disinformation Related to COVID-19

- Conspiracy Theories: Russia promoted conspiracy theories about the COVID-19 pandemic, including false information about the alleged dangers of vaccinations. The goal was to generate distrust towards the Polish government, medical institutions, and international organizations.

- Anti-Western Narratives: Russian media promoted the message that Poland and other Western countries were failing to manage the pandemic, emphasizing the supposed superiority of Russia’s crisis management model.

- Fomenting Social and Political Tensions

- Exploitation of Social Media: Russia engaged in disinformation campaigns on social media platforms to fuel social and political divisions in Poland. To this end, extreme narratives from both the left and right

of the political spectrum were promoted. - Manipulation on Social Issues: Russian propaganda attempted to influence Polish society by promoting controversial social issues, such as LGBT+ rights, migration, and religious matters, to provoke social tensions.

- Exploitation of Social Media: Russia engaged in disinformation campaigns on social media platforms to fuel social and political divisions in Poland. To this end, extreme narratives from both the left and right

- Disinformation Campaigns Related to Ukraine

- False Information about Refugees: Russia disseminated false information about Ukrainian refugees in Poland, suggesting that they pose a threat to the country’s security and economy. These narratives aimed to generate animosity among Poles towards Ukrainians and destabilize Polish-Ukrainian relations.

- Suggesting Polish-Ukrainian Conflicts: Russian media repeatedly suggested that Poland has hidden territorial ambitions towards western Ukraine, aiming to sow distrust between Poland and Ukraine and weaken the alliance between the two countries.

- (Dis)Information Attacks on Polish Media and Journalists

- Discrediting Independent Media: Russian propaganda campaigns often attacked independent Polish media, seeking to undermine their credibility and weaken their influence on public opinion. Media critical of Russia or exposing Russian intelligence activities were frequently targeted.

- Promoting Pro-Russian Media: Russia supported the development and activities of pro-Russian media in Poland, which aimed to propagate narratives favorable to the Kremlin.

- Exploitation of the Migration Crisis (the mechanism of forced migration used by Russia and Belarus against Poland and the Baltic states)

- Discrediting Poland Image

- Russian propaganda has frequently sought to undermine Poland’s credibility as a partner within the European Union, insinuating that Poland violates human rights or acts in a hostile manner towards its neighbors.

- In Poland, Russia has attempted to incite anti-European sentiments to weaken the bonds between Poland and the European Union and to provoke tensions between Poland and other member states.

- Poland has for many years been portrayed in Russian and Belarusian propaganda as an unstable, aggressive state responsible for the degradation of the international security system. To this end, it uses not only historical disinformation suggesting Poland’s complicity in causing World War II, but also contemporary disinformation narratives that portray Poland as a state preparing to attack Russia or Belarus, or as inhumane, where it exploits disinformation themes through disinformation campaigns about the violence (or even murder) of Polish officials against illegal immigrants based on the forced migration mechanism used against Poland [read more here].

- Russian propaganda portrays Poland as a state seeking to destroy Belarus [read more here].

- Historical lies and modern propaganda – Kremlin disinforms about Polish imperialism [read more here].

- Selected aspects of Alexander Lukashenko’s propaganda from an interview with Rossiya-1 in the context of the current propaganda campaign conducted by the Russians on social networks [read more here].

- Poland and the Baltics, Russian propaganda centers regularly attribute Russophobia as the main motivation for opposing Russian neo-imperialism. Since 2014, Russophobia has ceased to be a term used exclusively to describe xenophobic phenomena, and has become a tool for building propaganda messages. The term Russophobia

is increasingly common in the publications of major media outlets supporting the distribution of Russian propaganda and has become a permanent part of the canon of Russian propaganda journalism [read more here].

Conclusion

Russia’s propaganda actions against Poland aim to cause internal destabilization, weaken its international standing, and influence its political decisions. In response to these actions, Poland and its partners are taking steps to strengthen resilience against disinformation, educate the public, and develop international cooperation in the field of information security.

2. Supporting Extremism and Social Divisions

- Inciting Internal Conflicts: Russia actively supports narratives that can lead

to the polarization of Polish society, for instance, through provocations and inspiring extremist political groups on both the right and left of the political spectrum. - Radicalization Efforts: Exploiting social media to promote extremist ideologies and amplify existing tensions, e.g., in matters related to migration.

- Supporting the Far Right

- Nationalist Narratives: Russia has promoted nationalist and xenophobic narratives, often directed against national minorities, immigrants, and LGBT+ communities. The goal was to cause divisions in society and strengthen extremist attitudes among Poles.

- Disinformation and Anti-Ukrainian Propaganda: Russia sought

to support extremist right-wing groups by spreading anti-Ukrainian disinformation aimed at fueling hostility toward Ukrainian migrants in Poland. These narratives were particularly strong in the context of the conflict in eastern Ukraine and the migration crisis associated with the war. - Anti-Semitic Narratives: Russian media and propaganda channels sometimes fueled anti-Semitic sentiments, attempting to influence nationalist and extremist groups in Poland that could use these narratives to mobilize their supporters.

- Supporting the Far Left

- Promoting Anti-Capitalism and Anti-Globalism: Russia also sought to influence the far left by promoting anti-capitalist and anti-globalist narratives. To this end, Russia supported groups and initiatives that opposed globalization, neoliberalism, and institutions such as the European Union and NATO, portraying them as tools of oppression.

- Manipulation in Social Issues: Russian disinformation activities also encompassed social issues such as workers’ rights, access to healthcare, and the housing crisis. By supporting radical left-wing movements, Russia attempted to incite social discontent and introduce political turmoil.

Conclusion

In recent years, Russia has undertaken actions aimed at supporting and promoting extremism in Poland, both on the far right and the far left. These actions aimed to destabilize society, deepen political divisions, and weaken trust in democratic institutions. Here are some examples:

Fueling Anti-Immigrant Sentiments

- Disinformation Regarding the Migration Crisis: Russia actively promoted false information about migrants and their alleged suffering at the border, particularly in the context of the Belarusian-orchestrated migration crisis on the Polish-Belarusian border. The goal was to fuel fears, empathy, and divide Polish society on the issue of refugees, as well as to provoke tensions between Poland and its neighbors, including actions aimed at discrediting Poland on the international stage.

- Exploiting Extremist Movements for Destabilization: Russian propaganda channels often supported the anti-immigrant narratives of the far right, suggesting that Poland is being flooded by illegal immigrants, allegedly threatening national security and the country’s cultural identity.

Supporting Anti-System Movements

- Propagating Conspiracy Theories: Russia supported the development of conspiracy theories aimed at undermining trust in government and international institutions. Examples include spreading theories about alleged election manipulation, conspiracies of political elites, and false information about vaccinations and the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Supporting Anti-Government Movements: Russian media and internet trolls often supported anti-government movements, attempting to provoke political and social destabilization in Poland. These narratives were directed at both the far right and the left, depending on the context.

Inciting Social and Political Conflicts

- Exploiting Social Protests: Russia attempted to exploit social protests in Poland, such as anti-government protests or social movements related to women’s rights, to fuel divisions and strengthen radical sentiments. The narratives propagated by Russia often aimed to escalate conflicts and increase polarization in society.

- Infiltration and Support of Extremist Groups: Russia may have also attempted to infiltrate extremist political groups to strengthen their position and influence their actions in Poland. Supporting such groups could include both material and propaganda assistance.

Conclusion

These actions are part of a broader Russian strategy aimed at destabilizing countries it perceives as potential threats to its interests and weakening their internal cohesion and position on the international stage. In response to these threats, Poland and its partners are taking steps to strengthen resilience against extremism and disinformation, as well as educating the public on how to recognize and counter information manipulation.

3. Cyberattacks

Attacks on Digital Infrastructure: Russian hacker groups, often affiliated with the state, carry out attacks on Polish government institutions, media, and critical infrastructure. The goal of these attacks is not only to steal information but also to destabilize institutions. Spreading Malware: The use of ransomware and other types of malware to disrupt the operation of Polish companies and institutions.

Recent Cyberattacks

In the past two years, Poland has been the target of several significant cyberattacks aimed at disrupting the operations of government institutions, critical infrastructure, and private companies. Below are some of the most notable cyberattacks:

- Attack on Government Infrastructure (June 2021)

- Target: Government institutions and politicians.